Comparisons: Introduction (Multiple-Winner)

In the Evaluations (Party-List) chapter, CHPV is assessed in terms of its optimality, disproportionality and susceptibility to party cloning to highlight its own unique strengths and weaknesses. In this chapter, party-list CHPV is compared in turn to a variety of other multiple-winner voting systems to assess which is better for certain election profiles or scenarios.

Party-List CHPV versus other Multiple-Winner Voting Systems

One of the single-winner systems covered in the previous chapter is the Alternative Vote (AV). Its equivalent for multiple-winner elections is the Single Transferable Vote (STV). Here, a quota is set and any candidate reaching it is declared a winner. The excess votes of winning candidates and all the votes of eliminated ones are appropriately transferred to the remaining candidates until all the vacant seats are filled. STV voters express preferences for individual candidates rather than vote for a party as in party-list CHPV. However, in one important respect, they are directly equivalent. Both voting systems are ideally suited to concurrent elections in multiple few-winner constituencies.

Strictly, STV is a preferential voting system for electing individual candidates. It is not designed as a party-proportional one as candidates may or may not belong to any party. However, where voters in an STV election vote strictly along party lines (namely their highest preferences going to the candidates of their chosen party), the share of the seats between the parties is identical to that of a party-list one in which the same quota method is used. For simultaneous elections across multiple few-winner constituencies, STV nevertheless produces results that are largely party proportional; as does CHPV.

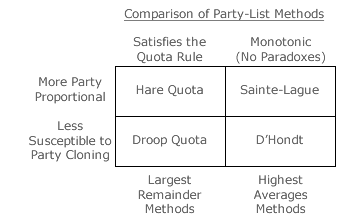

Party-list CHPV is then compared to each of the other major versions of the party-list method; see table opposite. There are two fundamental approaches to this method; one is the 'largest remainder' approach and the other type is the 'highest averages' one.

For the largest remainder approach, seats are allocated to each party according to how many times it meets a specified quota. Any remaining seats are awarded to the parties with the largest remainders of the vote. This is essentially a tally rounding-up exercise.

For the highest averages approach, each party tally is divided by a sequence of increasing divisors to generate a decreasing 'average' for the candidates on the party list according to their rank. Irrespective of party, those candidates with the highest averages are awarded the vacant seats.

The largest remainder methods are designed to satisfy the quota rule. This rule states that a party should receive either X or Y seats (where Y = X + 1 and X is an integer) when its exactly proportional but fractional seat entitlement is between X and Y seats. This is a fair criteria but one that allows paradoxes to occur. Where a party improves its fractional remainder but another party improves its remainder even more so, the 'remainder' seat may be won by the second party instead. Despite slightly improving its tally share, the first party here now gains one less seat!

In contrast, the highest averages methods are monotonic and do not exhibit such paradoxes. However, they no longer satisfy the quota rule and, in consequence, they are slightly less party proportional than their largest remainder equivalent (their horizontal neighbour in the table above).

The two most well-known largest remainder methods are the Hare Quota and the Droop Quota systems. The Hare Quota method is an optimally proportional voting system but it is susceptible to parties seeking to gain an unfair proportion of seats through cloning. Conversely, the Droop Quota is not vulnerable to party cloning but does not always generate an optimally proportional outcome. In few-winner constituencies, party-list CHPV proves to be comparable with the Droop Quota method in terms of party proportionality yet less susceptible to strategic nominations compared to the Hare Quota method.

The two most well-known highest averages methods are the D'Hondt and Sainte-Laguë systems. The Sainte-Laguë method is a highly proportional voting system but it is susceptible to parties seeking to gain an unfair proportion of seats through cloning. Conversely, the D'Hondt method is not vulnerable to party cloning but it is significantly less likely to generate an optimally proportional outcome. Party-list CHPV employs the highest averages approach. In few-winner constituencies, its performance is intermediate between these two other highest averages systems in each of these conflicting aspects. For concurrent elections in multiple few-winner constituencies, party-list CHPV hence offers a significant improvement in party proportionality compared to the D'Hondt method while avoiding the greater susceptibility to party cloning exhibited by the Sainte-Laguë method.

Finally, party-list CHPV is compared to some mixed member voting systems. Here, two different types of members are usually elected. One represents a local-area constituency having typically been elected in a single-winner plurality election. The other gains a wider-area seat through a multiple-winner party-list election. Wider-area seats are only awarded to a party when its share of local-area seats is less than its overall share of the vote. The allocation of such wider-area seats is designed to ensure, or at least to improve, the overall party proportionality of election outcomes.

Proceed to next section > Comparisons: Single Transferable Vote 1

Return to previous page > Comparisons: Summary (Single-Winner) 3