Comparisons: Plurality (First-Past-The-Post) and Anti-Plurality 1

Description of Plurality and Anti-Plurality

Plurality is a simple type of voting system with minimal voter input. Each voter just selects or indicates their most preferred candidate. After the votes for each candidate are counted, the one with the most votes - a plurality of the votes - wins. This single-round system is also known as first-past-the-post (FPTP). Alternative versions of plurality may involve two or more rounds with one or more of the lowest ranked candidates being knocked out at the end of each round. This section addresses only the single-round FPTP version of plurality. In anti-plurality elections, each voter casts a vote against their least preferred candidate instead and the candidate with the fewest negative votes overall wins.

These systems are not preferential ones as voters do not enter their full set of preferences onto the ballot but merely their first (or last) and only preference. However, for comparisons with GV, they can be treated here as both a preferential and a positional voting system by allowing all preferences to be expressed but then awarding all of them a zero weighting except for the first preference weighted at one (or the last preference weighted at minus one). For a more detailed and comprehensive description of plurality or anti-plurality, please visit the voting system section of Wikipedia or another reference source.

Properties of Plurality (FPTP)

FPTP can be treated as a positional system by equating it to GV with a common ratio of zero (r = 0). Hence, it satisfies all those voting system criteria that any positional system adheres to; namely, the summability, consistency, participation, monotonicity, resolvability and Pareto criteria.

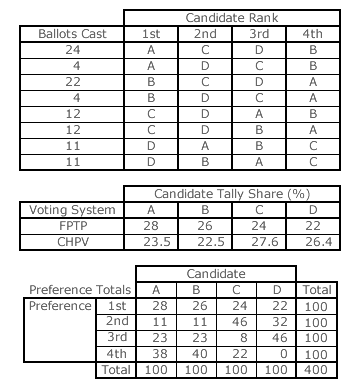

The tables opposite illustrate some other features of plurality.

FPTP satisfies the majority criterion but it does not require the winning candidate to achieve this 50% threshold. Getting at least half of the votes (first preferences) guarantees victory but frequently a winning share can be much lower. With N candidates, the absolute minimum for a winning tally share is just over 1/N. In the example opposite, the leading candidate (A) of the four has barely more than one quarter of the vote. A wins despite 72% of the voters preferring someone else.

This example also illustrates that FPTP favours polarized candidates over consensus ones. The highly polarized candidates A and B have the most first and last preferences while the strongly consensual candidates C and D have almost as many first preferences yet over three quarters of the second preferences between them. As plurality takes no account of voter preferences other than the first one, the two more polarized candidates rank above the two more consensual ones.

In contrast, CHPV satisfies the two-thirds majority criterion and requires winning candidates to have broader support in terms of high-rank (and not just top-rank) preferences. With identical voter input to the example election but with CHPV used in place of FPTP, a different outcome is produced. The two more consensual candidates are now ranked above the more polarized ones with C replacing A as the winner. A formal definition of a high-rank (above-mean-weighted) preference is given later in the Comparisons: Geometric Voting section.

In FPTP, 'minor' candidate supporters are regularly faced with the choice of whether to vote sincerely or tactically. If they vote sincerely for their no-hope candidate, they then have no affect on the election outcome and so 'waste' their vote. Whereas, if they vote tactically for one of the two perceived front-runners, they might then stop their less preferred one from winning. FPTP promotes tactical voting despite it requiring voters to anticipate how others will vote. Clearly, it is a risky business and one that suppresses 'minor' party support. Plurality alienates voters who cannot express their views on the crude ballot and so respond by either voting insincerely or not at all. In comparison, CHPV elections allow voters to express their full set of preferences so undermining the need and incentive for tactical voting. Even where attempted, tactical voting within CHPV is more challenging as it now requires voters to predict many of the numerous preferences of the other voters; not just their primary ones. Tactical voting in FPTP and GV systems is explored further in the Comparisons: Geometric Voting section.

When using FPTP (or GV with r = 0), vote splitting is a well-known major handicap. In the example election, a candidate who agrees with A on all issues bar one could enter and compete for the majority of the 28 votes for A. If more than two voters defect to this new candidate, then A loses this election to B who may have the polar-opposite opinions to A on all issues. When there is a crowd of candidates fighting to win support from the same pool of voters, then each is less likely to be elected than if a sole candidate had been nominated instead. Vote splitting not only generates self-harm but it also actively promotes voter misrepresentation. A comparison between vote splitting in FPTP and in CHPV elections, is addressed later in the Comparisons: Geometric Voting section.

Proceed to next page > Comparisons: Plurality (FPTP) and Anti-Plurality 2

Return to previous page > Comparisons: Introduction (Single-Winner)