Evaluations: Introduction (Ranked Ballot)

Generally, elections are either used to choose a single winner from several candidates or options or used to choose a limited but representative set of many winners. Ranked ballot elections are suited to selecting single winners while party-list systems are applicable to multiple-winner elections. This chapter concentrates on GV and CHPV as single-winner ranked ballot voting systems. Both GV and CHPV can fully translate the individual voter ranked ballots into one collective rank-ordering of the candidates. As they do not merely differentiate one winner from the remaining losers, they can sometimes be used to elect more than one winner. Nevertheless, the analysis of ranked ballot GV and CHPV in this and subsequent chapters is restricted to single-winner outcomes only.

As GV and CHPV are preferential systems, it is via the ranked ballot that voters express their relative preference for each of the competing candidates. As positional voting systems, the count process is literally just that. So, such elections are both simple and transparent. But are they fair? Do they generate sensible results? Can they be manipulated? Are they better than other systems? In this chapter, ranked ballot GV and CHPV are evaluated against various independent voting system criteria to assess their own unique strengths and weaknesses. Comparisons with other rival single-winner voting systems is addressed later in the Comparisons (Single-Winner) chapter.

Ranked Ballot GC and CHPV Elections

There are a number of standard voting system criteria that examine whether any particular voting system passes or fails various aspects of fairness and legitimacy. No system can pass all of them, so it is a question of which ones GV and CHPV comply with or fail to satisfy and why. In common with other positional voting systems, most of the general criteria associated with summability, consistency, participation, monotonicity, resolvability and unanimity are passed. A candidate with a majority of first preferences will not necessarily win using GV as the threshold for guaranteed victory rises with the common ratio used. However, when using CHPV, a candidate acquiring over two thirds of first preferences always wins. Where GV and CHPV do struggle is in satisfying the relevant independence criteria that relate to the manipulation of election outcomes by parties or sets of candidates.

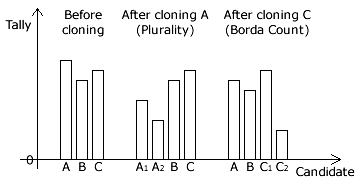

In elections for a single winner, parties should only nominate one candidate each. However, by introducing more than one (a strategy called cloning), election outcomes can often be altered; see the three-party example opposite. In the initial (before cloning) election, candidate A has the largest tally and so wins the single seat.

Plurality (or first-past-the-post) is not categorised as a positional voting system but it can be analysed as such; namely by awarding one point to the first preference and zero to every other preference. If party A here was to replace its one candidate by two (A1 and A2), then it could lose this election to party C. This change of outcome results from the previous tally for party A now being split between its two candidates and neither alone having sufficient to beat C. Such 'vote splitting' clearly produces self-harm for the cloning party.

However, using the Borda Count positional voting system, such cloning has the opposite effect. If say party C now added a second candidate instead of party A, then C supporters can rank C1, C2, A and B in that order on their ballots instead of previously just C, A and B. Clone C2 is added simply to push A and B down one place in the rankings. This is called 'burying'. This depresses the tally for A and B in relation to C1 and thereby C1 may gain unfair victory; as in this example.

This deliberate act of manipulation is called teaming. With no hope of winning, clone C2 is only nominated to 'team' up with C1 to try to defeat A and B. Candidates may be nominated for sincere or 'strategic' reasons. Although strategic nominations are a form of cheating, they are still legitimate as it is impossible in practice to establish true motivations for standing. Even Borda himself said that his system was intended for "honest men" only.

GV has a common ratio (r) that extends between zero and one. For plurality elections and for GV ones with r = 0, vote splitting is prevalent but teaming does not occur. For the Borda Count and for GV with r → 1, teaming is a major problem but vote splitting does not exist. As the common ratio increases from zero towards one, the effects of vote splitting lessen but those of teaming worsen.

As the common ratio for CHPV has the mid-range GV value of r = 1/2, it is perhaps not surprising that CHPV achieves a reasonable counterbalance between these two conflicting features. Indeed, although the CHPV system cannot itself prevent teaming, voters opposed to any cloning can nevertheless thwart such attempts to win unfairly. An extensive evaluation of cloning, vote splitting and teaming when using GV is conducted in this chapter.

Proceed to next section > Evaluations: General Criteria

Return to previous page > Description: Summary