Comparisons: Single Transferable Vote 2

Properties of the Single Transferable Vote

STV clearly satisfies the majority criterion as any quota will be 50% or less for elections with two or more winners and any candidate gaining over 50% must therefore win a seat. However, it fails the monotonicity and summability criteria. Given its complex algorithm, the count may require many rounds of counting and take a considerable time to complete. There can be up to N+1-W rounds of counting with just one less candidate present in each successive round.

Also, like the Alternative Vote, the STV algorithm is not deterministic. In each round, two or more candidates may tie for last place. The random selection of one of these candidates for elimination means that a different candidate can be eliminated if the process is rerun. This also means that a different winner can emerge after the final round of counting.

Although STV fails the Independence of Irrelevant Alternatives criterion, it does meet the Independence of Clones requirement. So parties avoid the need for slates that list their multiple candidates in preferred rank order as vote splitting and teaming do not occur.

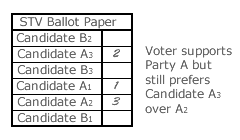

When voters loyally express their highest preferences for the candidates of a particular party (see example opposite), STV is widely recognised as a voting system that generates a high degree of party proportionality in multiple-winner elections. However, voters are nevertheless free to express their candidate preferences regardless of party affiliation or of any suggested rank-ordering of candidates within a party (see example opposite again).

To reiterate, STV preferences are awarded to candidates and not to parties. This means that not only are parties competing against each other but that candidates within each party are also competing amongst themselves. This gives considerable power to the electorate over who represents them.

An STV election is typically held with three to five vacant seats to be filled. For regional, national or other large membership bodies, concurrent STV elections are usually held in numerous local few-winner constituencies. By this means, all the winning candidates have the same status on the representative body. They also all have the same responsibilities towards their local electorates.

Where voters strictly cast candidate preferences according to the wishes of their party, the outcomes are essentially equivalent to the relevant largest remainder method of the party-list system. The Hare and the Droop (or Hagenbach-Bischoff) largest remainder methods are each addressed in later sections of this chapter.

For an explanation of why the Droop quota is nowadays used in preference to the Hare quota for STV elections, please refer to the Party-List ~ Hare Quota and Party-List ~ Droop Quota sections.

Comparison with Party-List CHPV

Party-list CHPV is a simple, quick, transparent and deterministic method that requires just a single round of vote counting before candidate averages are calculated. In contrast, STV employs a complex, lengthy, opaque and non-deterministic algorithm that requires many rounds of counting. However, unlike CHPV contests, teaming and vote splitting does not occur in STV elections.

In multiple-party multiple-winner elections, large electorates in both STV and party-list CHPV elections are subdivided into numerous local few-winner constituencies. There is only one type of victor as each winner has the same status and set of electoral responsibilities. Both STV and CHPV are also capable of generating largely party-proportional results overall and so, despite very different algorithms, often produce quite similar outcomes.

In STV elections, voters are free to cast preferences for candidates irrespective of their party allegiance. Parties hence nominate candidates who are likely to attract the broadest popular support. In closed-list CHPV elections, voters can only cast one vote for their chosen party. However, supporters of a party may additionally be allowed a free list for choosing which of their party candidates are to fill the vacant seats already won by their party. Ranked ballot CHPV is an obvious choice for this free-list selection process.

Being based on single-status seats in multiple few-winner constituencies and allowing voters to rank their party candidates using a ranked ballot, this form of CHPV has perhaps more in common with STV than with any other rival voting system; even its sibling party-list ones.

Proceed to next section > Comparisons: Party-List

Return to previous page > Comparisons: Single Transferable Vote 1