Evaluations: Clones, Teaming and Independence Criteria 5

Types of Clones and Slates

Looking now at teaming in more detail, the preceding examples in this section demonstrate that introducing a clone can be a risky business. Depending on the electoral method chosen and on how voters strictly rank clones - when they cannot discriminate between them - either teaming or vote splitting could easily result. Without knowing how voters will actual rank the clones or without telling them how to, then outcomes can be unpredictable.

Using the common ratio as a variable, GV is able to represent an unlimited range of positional voting systems. For the purposes of the GV evaluation, it is important to differentiate between clones that cause teaming and ones that split the vote. If a clone set prompts vote splitting and suffers as a consequence, then it only has itself to blame. However, if it promotes teaming, it is seeking to gain an unfair advantage and should ideally be stopped from achieving its goal.

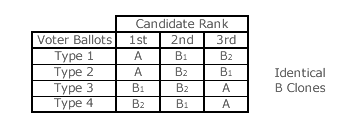

The ballot types from the preceding example on page 3 that produced the vote splitting effect are repeated in the table opposite. For GV, a clone is 'identical' when it is just as likely to be placed before any other member of the clone set as after it; as here. Hence, identical clones all have the same average rank position and hence the same tally in the election. As adding such clones also adds more rank positions, both their average rank and relative tally therefore decline. When there is a large number of voters and none are told how to rank the clones, then vote splitting due to identical cloning will occur quite naturally by default.

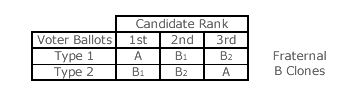

The ballot types that instead produced the teaming effect are also repeated in the new table opposite. For GV, clones are 'fraternal' when they are always ranked in the same order in adjacent positions by voters strictly preferring that clone set to other candidates; as here. Hence, the top-ranked clone will retain its original rank position while the lower-ranked one(s) push the other candidates down the rankings. For this teaming to succeed, supporters of the clone set must however be told how to rank 'their' clones so that they all use the same rank order.

This can be engineered by a party instructing its supporters to vote loyally for a rank ordered 'slate' of its own otherwise identical candidates. In this example, B has issued a slate ranking B1 ahead of B2. Normally, a slate issued by a party or clone set is called a 'forward' one. In later examples, competing parties issue a 'reverse' slate where the rankings are in strict reverse order to the 'forward' one; so here B2 is ahead of B1. A party slate should not however be confused with a party list. A unofficial slate rank orders several clone candidates for a single-winner election while a party list declares its official N candidates (in rank order) for an N-winner election.

In practice, cloning is never quite as clear cut as in a mathematical model. Two candidates may be very similar but not identical. If they stand against each other over say a 'minor' issue of disagreement, then they could each suffer defeat as a result of vote splitting. Also, teaming is unlikely to be maximized due to individual supporters being able to discriminate between similar but not identical candidates and then not being fully loyal to the party slate. Nevertheless, a mathematical evaluation using perfect clones gives a very good indication of how vulnerable a voting system is to strategic nominations. As vote splitting due to identical cloning is entirely a self-inflicted penalty, it is the vulnerability of GV to fraternal cloning and its ability (if any) to thwart such teaming attempts that really matters.

Proceed to next page > Evaluations: Clones & Teaming 6

Return to previous page > Evaluations: Clones & Teaming 4