Evaluations: Party Cloning 2

Susceptibility to Party Cloning

An Optimally Proportional Voting (OPV) system always fully minimises the disproportionality in any outcome. By definition, it always produces the optimum party-proportional result. Hence, it has 100% optimality. Compared to this ideal benchmark, CHPV achieves an optimality of over 70% for elections with two or three parties competing for no more than five seats. However, compared to this OPV benchmark, is CHPV more or less susceptible to party-cloning strategic nominations?

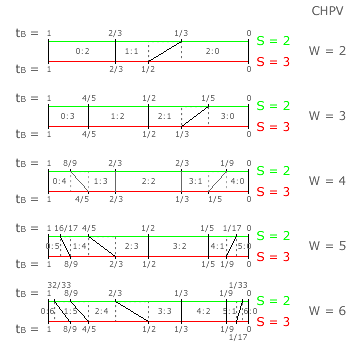

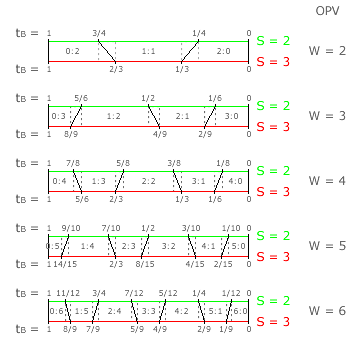

In order to answer this question, the previous OPV figure showing the pre- and post-cloning tally share thresholds for the two-winner (W = 2) seat share domain boundaries is repeated below (top-left). The only change here is that the tally shares now refer to the cloning party B. All the other figures displayed below are constructed using the same approach of comparing the two-party map to the relevant three-party one where the two clone parties have an equal vote share. This set of figures covers both OPV and CHPV elections with up to six winners.

Regarding OPV, one in six of all possible outcomes are altered by party cloning. This is independent of the number of winners. The highlighted white areas decrease in width as their number increases such that the sum of their identical widths remains constant at 1/6.

Another obvious feature of the OPV figures is that the tally share thresholds for party B are either raised or lowered by the act of cloning. When the cloning party raises its own threshold for gaining seats by cloning, it is clearly harming itself. But when the cloning party lowers its own threshold, its cloning attempt is successful. Within the highlighted white areas, rising thresholds have positive slopes and falling ones have negative slopes. For an even number of winners, party cloning is as likely to be harmful as it is to be helpful. For a odd number, it is slightly more likely to be harmful than helpful. To benefit from cloning, a party has to weigh up its prospects very carefully.

For CHPV, a very different picture emerges from the above figures. Irrespective of the number of winners, attempts to gain one seat through cloning are counterproductive as it raises the (right-most) threshold. Also, attempts to gain two or three seats unfairly by cloning fail too as the two (adjacent) thresholds are unchanged. For two or three winners, party cloning is never helpful. However, any and all remaining (left-most) thresholds are lowered by cloning. So provided the cloning party has insufficient support to convert three seats into four through cloning, then party cloning within two-party CHPV is never successful; regardless of the number of seats to be won.

Although CHPV can never better OPV in terms of optimality, it is better in thwarting all attempts at party-cloning strategic nominations where the cloning party has the smaller vote share (t < 1/2) and no more than six winners (W ≤ 6) are to be elected. As stated previously, 'few-winner' CHPV elections are restricted to a maximum of six anyway. In contrast, there is always an incentive to clone for a party seeking to convert one seat into two through cloning in any two-party multiple-winner OPV election.

From the previous section, having five seats in a party-list CHPV election with an unknown number of parties intending to stand would most likely maximise its optimality. For up to five winners, any cloning party would need to get over two thirds of the vote (t > 2/3) to gain any unfair advantage in seats over the other party. Hence, having no more than five seats severely curtails the chances of party-cloning strategic nominations being successful while simultaneously maximising optimality. There is no trade-off here as both parameters are better with up to five winners than with six or more.

Proceed to next section > Evaluations: Proportionality

Return to previous page > Evaluations: Party Cloning 1